Travelling through the flat landscape of the Gwent Levels, the long lines of electricity pylons and their cables are a stand-out feature. An intrusive eyesore, or a thing of elegant beauty? History RAT, Marion Sweeney, explores their history.

Looking across the lagoons at Newport Wetlands (C Harris)

A three-phase high-voltage electric power distribution system had been developed by Nikola Tesla at the end of the nineteenth century. In the 1920s, Britain’s electricity was provided by several separate regional companies, and the coal-fired power stations supplying them varied greatly in efficiency and reliability. Growing demand from domestic consumers and industry put pressure on these unconnected networks.

In 1925, the Glasgow industrialist, Lord Weir, was tasked with solving the problem. Along with Charles Merz (of Merz and McLellan, a leading British electrical engineering consultancy), he recommended the development of a nationwide electricity grid or ‘gridiron’ to connect the 122 most efficient power stations. This plan was enshrined in law by The Electricity (Supply) Act of 1926, and the Central Electricity Board was created to oversee development of the National Grid. This was to be an alternating current system operating at 132 kV, 50 Hz.

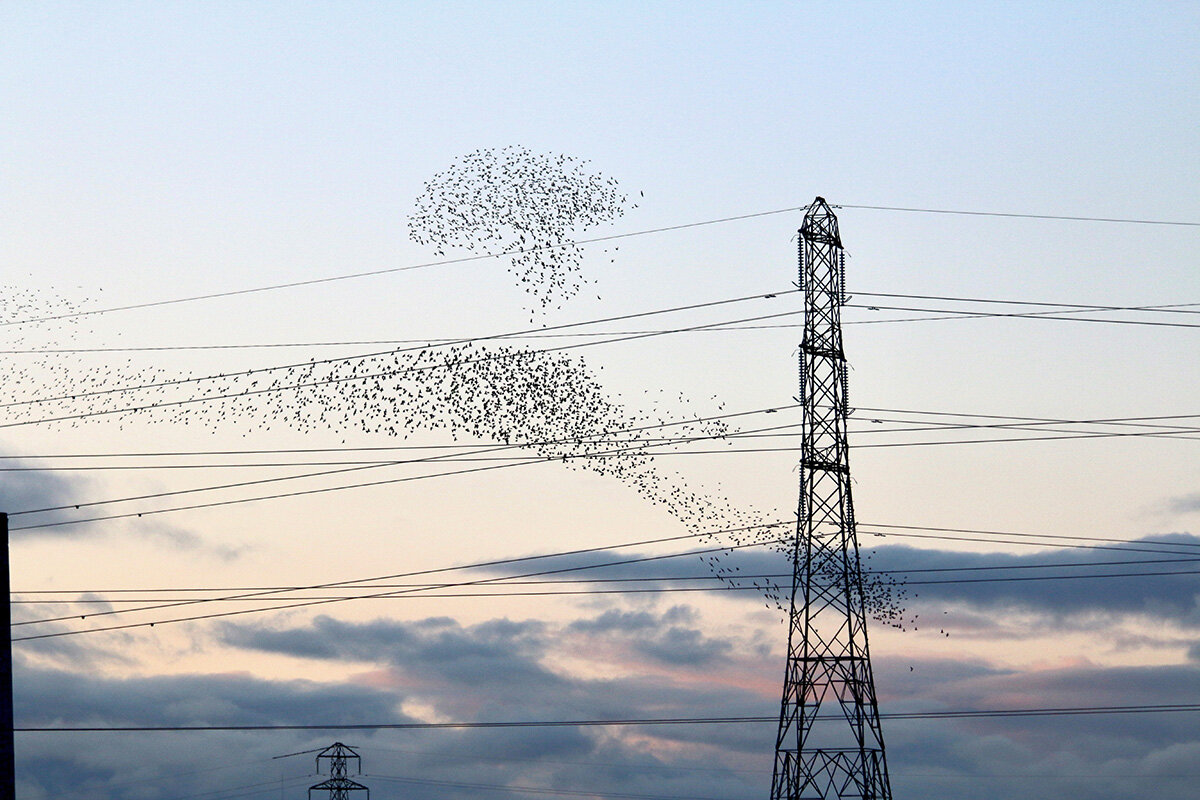

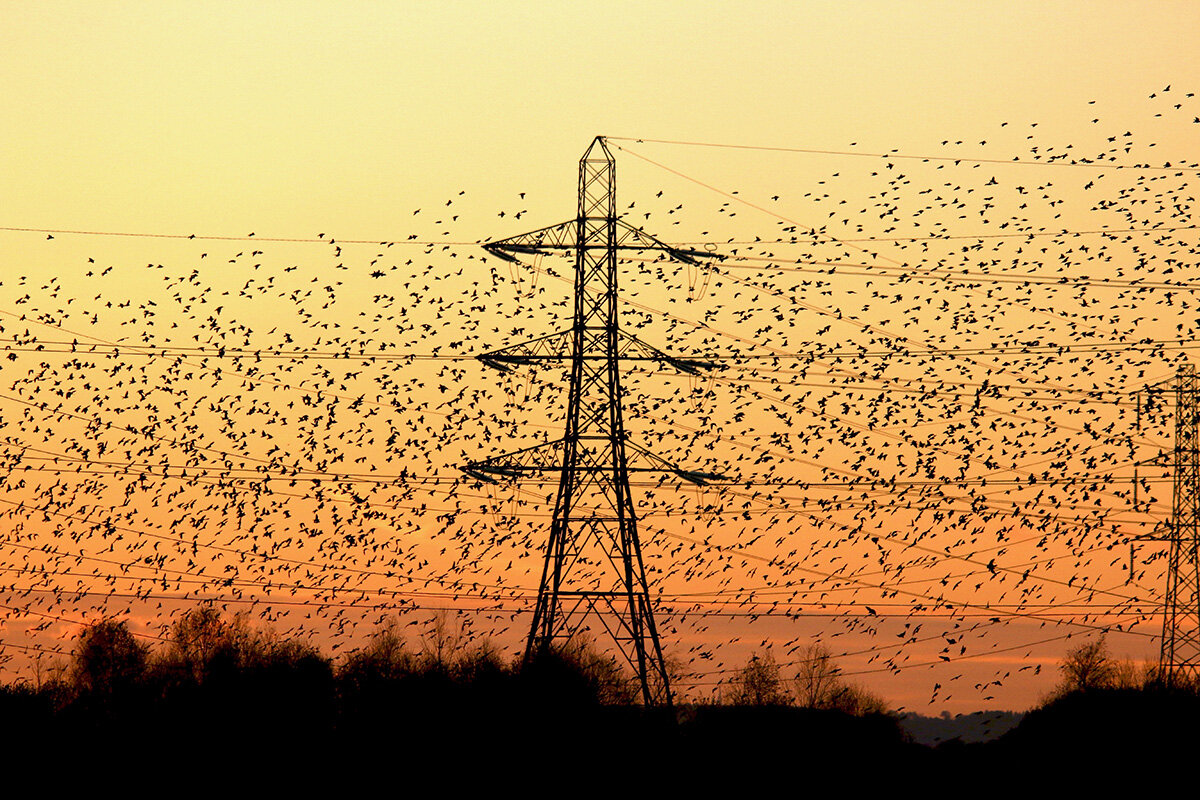

Pylons at Newport Wetlands (Marion Sweeney)

The only cost-efficient way to create the grid was to use overhead power cables, but this raised another problem, how the required 4,000 or so miles of cabling would be supported. This challenge was given to the classical architect Sir Reginald Bloomfield, who selected the final design from a competition run by the Central Electricity Board in 1927. The design he chose was a latticed A-frame structure submitted by the American firm, Milliken Brothers, a design familiar to us today. It appealed to Sir Reginald’s anti-modernist views. He named the new towers ‘pylons’ after the Egyptian for ‘gateway’. This reflected both their appearance, and the idea that they would provide a ‘gateway’ to a reliable electricity supply for the UK. The more correct term for them is suspension, tension, or transmission towers. The compromise Sir Reginald’s chosen design achieved between form and function contrasts to the more brutalist transmission towers seen in mainland Europe.

The first pylon in the UK was constructed in 1928 in Bonnyfield, Falkirk. Over the next ten years, their numbers rapidly increased, and the grid was operating as a national system by 1938. In addition to the pylons that form straight lines across the countryside, terminal towers are located at each end of the route, while tension or angle towers enable the route to be realigned if necessary.

From the beginning, electricity pylons were controversial features of the landscape, particularly in areas prized for their natural beauty. The year 1936 saw a pylon ‘war’ in the Lake District when three local authorities petitioned against overhead lines from Kendal to Staveley as these would cross the beauty spots of Scout Scar and Cunswick Scar. Despite a spokesman from the Central Electricity Board remarking that ‘The steel towers carrying the cable would lend a certain amount of dignity to a somewhat uninteresting prospect’, the protests continued. Eventually the protestors’ appeal was successful and the line was re-routed elsewhere, thus saving Scout Scar from ‘a giant latticework intruder’. This protest, and other similar campaigns throughout the UK, illustrated the growing conflict between industrialisation and preservation of the landscape.

There was also the desire of a growing urban population to have access to unspoilt areas for recreation. These pressures came to a head during the 1930s, eventually leading to the creation of Britain’s National Parks. The first of these were the Peak District, the Lake District, Snowdonia and Dartmoor in 1951, with six more regions to follow by the end of that decade.

Reaction to ‘the march’ of the electricity pylons was not all negative, as many appreciated the improved electricity they supplied. Some admired their stark beauty, seeing them as a symbol of progress. A group of modernist poets, including Stephen Spender and W. H. Auden, became known as the ‘Pylon Poets’, using pylons as their inspiration, which is perhaps ironic given Sir Reginald Bloomfield’s anti-modernist views.

In May 1958, the Western Mail reported that ‘Britain’s electricity “supergrid” costing £72 million, will span two rivers – the Severn and Wye – to reach South Wales. And it will be one of the engineering wonders of the age.’ The Central Electricity Generating Board (as it was then known) dismissed public criticism stating that ‘the supergrid must stride across the countryside, because of the cash outlay. It costs £25,000 a mile for an overhead line, and £300,000 to £400,000 a mile for laying cables underground.’

The RSPB Newport Wetlands Nature Reserve boasts a fine array of electricity pylons due to its proximity to the Uskmouth Power Station. Built in 1959, this is currently coal-fired, but plans are in development to replace the coal with waste-derived fuel pellets. The pylons and their associated cables give a unique backdrop to the reserve and offer popular perches to some of the resident birds. Cormorants are often seen high on the towers, and during the autumn and winter, starlings line the wires as they gather in preparation for their murmuration. Fortunately, the birds are safe from electrocution, as in this position, electricity does not flow through their bodies because they are not in direct or indirect contact with the ground.

Today, the UK has over 90,000 electricity pylons, and for the first time in over a hundred years, a new design is being rolled out, the so-called ‘T-pylon’, a shorter and more streamlined structure. Another change underway is the removal of pylons in areas of outstanding natural beauty, replacing them with underground cables. Planning permission has already been granted for this in Snowdonia and the Peak District, with other areas to follow.

![Wesleyan Methodist chapel Castleton (Penny Gregson)[2].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a1d5fb38a02c70db7c34f81/fe4960cd-db68-469d-8411-f5e21327e383/Wesleyan+Methodist+chapel+Castleton+%28Penny+Gregson%29%5B2%5D.jpg)